The Concert For Bangla Desh

by: Bill Harry

In March 1971, following political problems and strife between the various regions in Bangla Desh, in the eastern half of Pakistan, Pakistan’s ruling General sent in the army to deal with any opposition. Then, in December 1971, a cyclone swept across the region, causing immense devastation.

There was a complete breakdown throughout the country with no clean water, no food, no adequate shelter and in addition to the fear of military suppression there was the hunger and disease, rife in the country.

In June 1971 while in Los Angeles, he decided to try to raise some money, perhaps a few thousand dollars, to help the people of Bangla Desh. At the time he was completing the film ‘Messenger From The East’ with George and he asked George if he would help him with a benefit show, perhaps acting as a compere for the night.

Ravi gave George some magazines with articles about the famine and George decided that a small-scale concert wasn’t good enough. As he was to remark later, “The Beatles had been trained to the view that if you’re going to do it, you might as well do it big.”

George approached Allen Klein and instructed him to book the 20,000-seater Madison Square Garden in New York. As soon as news of the concert was announced, the seats sold out and a further show was arranged for the same night, Sunday August 1, which also sold out almost immediately. Both shows had sold out within six hours.

George also contacted Apple’s A&R head, Phil Spector with instructions to record the concert and he approached Apple Films to document the event.

A number of George’s immediate musician friends became involved – Badfinger, Billy Preston, Jesse Ed Davis, Carl Radle, Klaus Voormann and Jim Keltner.

He immediately contacted Ringo who took time off from filming the Western ‘Blindman’ to travel to New York for rehearsals. John and Yoko had been planning to travel to New York to complete their recording of an album in July, so John agreed to appear. Even Paul gave a tentative approval of the project and seemed willing to appear. However, it seems that he wanted some of the different business difficulties resolved first, which couldn’t be done at the time, so he pulled out.

When John arrived with the omnipresent Yoko, George had to explain that he only wanted John to appear on the show and not Yoko. She was furious and created such a violent argument that John’s glasses were broken. John was so upset he immediately left and took the first plane to Europe, ending up in Paris!

It’s a pity that posterity was denied John’s appearance at this highly important concert due to Yoko’s determination to cling like a limpet to everything John did, proving that he was unable to carry on a solo career like the other ex-members as Yoko insisted on being involved in all his records and concerts.

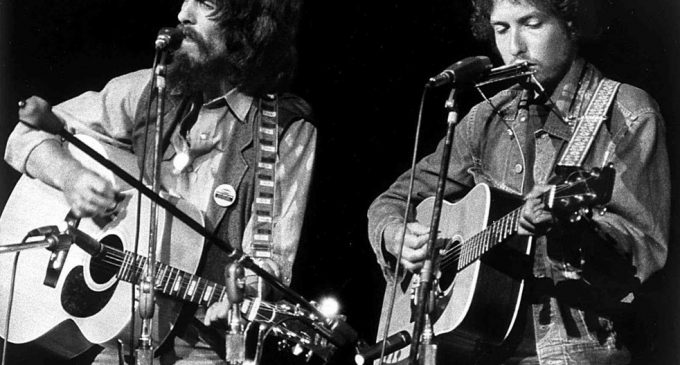

Dylan’s appearance was kept secret until he actually walked on stage, which created an absolute sensation, as everyone had believed he’d retired from the music scene.

This coup hadn’t been easy for George to arrange as Dylan had been missing rehearsals, then phoning George to say he couldn’t handle the pressure and wouldn’t appear after all.

George also had difficulties regarding Eric Clapton’s participation. Like Dylan, Clapton hadn’t made any appearances for a year and he was hooked on drugs. In fact, as soon as he arrived in New York he sent his girlfriend Alice Ormsby-Gore out onto the streets to score some heroin for him. He was so ill he was unable to attend rehearsals the night before the concert and Jesse Ed Davis was on stand-by as his replacement.

Fortunately, both Dylan (George was on tenterhooks because even at the start of the concert he wasn’t sure whether Dylan would turn up) and Clapton (who had treatment by Doctor William Zahm earlier that day) were able to perform.

The concert began with George introducing Ravi Shankar for a set of Indian music. Ravi played sitar and his other musicians were Ali Akbar Khan on sarod and alla Rakha on tabla and Kamala Chakravarty on tamboura.

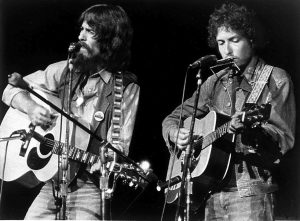

The next to appear was George, who opened his set with ‘Wah-Wah.’ His backing musicians were Eric Clapton on guitar, Ringo Starr and Jim Keltner on drums, Leon Russell on piano, Billy Preston on keyboards, Jesse Ed Davis on electric guitar. Jim Horn leading a brass section, Klaus Voormann on bass, Claudia Linnear leading a nine-piece Gospel choral and three members of Badfinger on acoustic guitars.

George then introduced Dylan, saying “I’d like to bring on a friend of us all – Mister Bob Dylan.’

A bearded Dylan, dressed in denim jacket and jeans opened with ‘A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall.’ He next performed ‘Mr Tambourine Man’, ‘Blowin’ In The Wind’, ‘It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry’ and ‘Just Like A Woman.’

On the last number he was joined by George on guitar, Ringo on tambourine and Leon Russell on bass.

Following the two shows there was a celebration party. The following morning, when George read the positive reviews in the local papers, he sat down and wrote the song ‘The Day The World Gets Round.’

The full listing of artists was: Rock performers: George Harrison, Eric Clapton, Jesse Ed Davis and Don Preston on guitars. Pete Ham, Tom Evans and Joey Molland of Badfinger on acoustic guitars; Mike Gibbins of Badfinger on percussion. Billy Preston on organ. Leon Russell on piano and bass. Carl Radle and Klaus Voormann ob bass. Ringo Starr on drums and tambourine. Jim Keltner on drums. Bob Dylan on harmonica and acoustic guitar. Jim Horn, Chuck Findley and Ollie Mitchell on horns. George Harrison, Billy preston, Ringo Starr, Leon Russell, Don Preston and bob Dylan on vocals. Alan Beutler, Marlin Green, Jeanie green, Jo Green, Dolores Hall, Jackie Kelso, Claudia Linnear, Lou McCreary and Don Nix on backing vocals. Indian music section: Ravi Shankar on sitar. Ali Akbar Khan on sarod. Alla Rakah on tabla and Kamala Chakravarty on tamboura.

A particularly disappointing aspect was that although all the artists were donating their services to aid the poor and starving people of Bangla Desh, the tax inspectors of both Britain and America wanted their pound of flesh. They demanded the full tax from all the proceedings, uninterested in the fact that this was literally taking the food out of the mouths of a starved and battered people. The idealistic George was disillusioned by this intransigence from the tax authorities, but he signed a personal cheque to cover the demands.

The concert itself brought in a quarter of a million dollars and the album and film generated millions, yet there seemed to be some problems regarding these funds. An article in New York magazine implied that Allen Klein had absconded with some of the money and Klein responded with a multi-million dollar lawsuit, which he then dropped. There was a lot of red tape involved before the people of Bangla Desh began to receive the money.

‘The Concert For Bangla Desh’ (it was spelt as two words on the concert, album and film, although the name was to become a single word) was the template for all the great charity rock shows to follow, such as ‘Live Aid’. Considering the impact and influence of the event, and also all the other charity work George was involved with, it’s difficult to equate the fact that he was never recommended for any honours apart from his MBE, the lowest order of knighthood. Bob Geldof. For instance, received a knighthood for ‘Live Aid’ and comedians, pop singers and numerous other people in the music business have been awarded CBEs, OBE’s and even knighthoods, but George, a vital member of the most celebrated music group of all time, a great charity donor, someone who had brought prestige and honour to Britain, in addition to the wealth, plus the fact that he virtually revived the British film industry with HandMade Films, was never considered for anything following the 1966 MBE honours which shows the lack of foresight of those who recommend the awards.

There are no comments at the moment, do you want to add one?

Write a comment