Mersey Beat Makes Its Debut by Bill Harry – (McCartney Times Exclusive)

Mersey Beat Makes Its Debut

(by Bill Harry, billharry@aol.com)

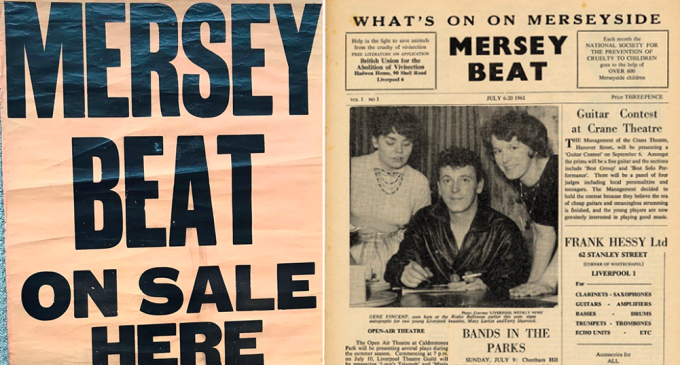

The first issue of Mersey Beat made its debut on 6 July 1963, produced from a tiny little office in the attic of 51a Renshaw Street, above David Land, the wine merchant.

While at the Junior Art School I launched a duplicated magazine called Premier and when I entered Liverpool College of Art, I issued a duplicated magazine simply called Jazz. I was next asked to help edit the university charity magazine Pantosphinx and also a music magazine for the Frank Hessy music store called Frank Comments.

Page 2 sported the famous John Lennon piece – a picture of me which was a block I’d obtained from Pantosphinx magazine; a small piece on the Undertakers (sharing the honours with the Beatles as the first band to have their biog in Mersey Beat).

Page 3 Included details of the Liverpool Show, a major annual event in Wavertree, together with a brief biog of the Big Three, a piece on the Country Music Club the Black Cat Club, above Sampson & Barlow’s Restaurant in London Road and also a piece on ‘The Black Cats’ group.

Page 4 had the Swinging Cilla article and a piece on the film ‘Spartacus’, with two blocks of pictures from the film which I’d borrowed from the Odeon Cinema, there was an advert for Hambleton Hall, the first advert for a local music venue to appear in Mersey Beat.

Page 5 had a cartoon by Mike Isaacson, a friend of mine from my Art College Class (he’d also gone to Quarry Bank school with John Lennon). It was a block I’d borrowed from Pantosphinx. The cartoon headed ‘Mersey Roundabout’, a column by Virginia with lots of local gossip. Half of the page was taken up by an article on the Cavern and Page 6 was a full-page Cavern advertisement.

How Cilla Got Her Name.

The article on Page 4, ‘Swinging Cilla’ was responsible for Cilla Black’s name. The second paragraph begins with the words ‘Cilla Black is a Liverpool girl who is starting on the road to fame.’

I remember Virginia and I going down to the State Ballroom one evening when I was putting the first issue together and asking Cilla if she had the fashion column she promised me. She was with her mate Pat Davies (Ringo’s girl friend at the time) and Cass & the Cassanovas were on stage.

When I got back to the office I began working on the text for the first issue and then began to type out a story on Cilla. When it came to writing down her surname, my mind went blank. I knew it was a colour but forgot which one. I took out the piece of paper with Cilla’s fashion column in it (which was published in Issue No. 2), but she hadn’t signed it. The column was all about colours in fashion and went from white to black. Looking at it, I decided on the black. I was wrong. Her name was Cilla White!

After Mersey Beat was published, Cilla came into the office and told me that I’d got her surname wrong – but she liked it so much she decided to call herself Cilla Black from now on, despite her father’s anger at the misprint!

Late in 1963 when Brian Epstein signed her, her publicity machine created a completely false story that on signing her Brian decided to change her name from White to Black. They obviously weren’t aware that the name change came in this first issue, well before he even knew her and over two years before he signed her. Later, it was some of the other statements made by Brian or issued by his publicity arm, which made me realise for the first time how actual facts could be twisted or invented and thus change what was to become part of musical history.

An Origin Of The Dubious.

When John Lennon and I were sitting together in Ye Cracke, our art college ‘local’ (a public house frequented by students of Liverpool College of Art), I mentioned that I’d heard he wrote poetry. At first, he demurred. It wasn’t the sort of hobby a ‘macho’ type would admit to. After I’d pressed him, he then took some pages of notepaper out of his pocket and showed them to me. I was pleasantly surprised. I’d expected a pastiche of ‘Beat Generation’ poetry, which was all the rage at the time. Yet this was a rustic poem, lusty and down to earth, completely English in its essence:

Owl George ee be a farmer’s lad

With mucklekak and cow

Ee be the son of ‘is owl Dad

But why I don’t know how

Ee tak a fork and bale the hay

And stacking-stook he stock

And lived his loif from day to day

Dressed in a sweaty sock

One day maybe he marry be

To Nellie Nack the Lass

And we shall see what we shall see

A-fucking in the grass

Our Nellie be a gal so fine

All dimpled wart and blue

She herds the pigs, the rotten swine

It mak me wanna spew!

Somehaps perchance ee’ll be a man

But now I will unfurl

Owl George is out of the frying pan

’Cos ee’s a little girl.

It was in 1960 when I decided to found Mersey Beat and report on the local scene, that I commissioned John to pen a short biography of the band. Some months later we were sitting in the Jacaranda when he handed it to me, shortly before the group set off on their second trip to Hamburg. It was something totally unexpected. Its sheer wackiness delighted me. I immediately ordered him coffee and jam toast! (It was 1d extra to have jam on your toast!).

The piece appears on page 2 of the first issue. The humour of it appealed to me. It was the time of the Goons (who regularly said, ‘you rotten swine’) and at Junior Art School I’d been involved with some friends, in what we called the Natty Nut Society. I was also interested in the Nonsense Novels of Stephen Leacock (as was Paul McCartney – and John had borrowed a copy of the book from the Quarry Bank school library).

As a result, I decided to print the biography as John had written it, without altering a single word. It had no title, so I made up the heading ‘Being A Short Diversion On The Dubious Origins Of Beatles (Translated From The John Lennon)’.

As the biography may be esoteric to some visitors, I will translate even further from the John Lennon. The man with the beard cut off is Allan Williams, the owner of the Jacaranda club, a coffee bar in Slater Street where we used to hang around during our Art College days (mainly me, John, Stuart and Rod Murray). Allan had recently shaved his large black beard off. He was also the man who first booked them into Hamburg.

The Casbah was a club in West Derby run by Mona Best, mother of Pete Best – and the club where the Beatles, in their Quarry Men incarnation, had enjoyed their first residency.

John’s peculiar spelling of Paul’s surname (he wrote “Paul (who is called McArtrey, son of Jim McArtrey, his father) …” caused some problems later on as I presumed it was the correct spelling and used it in a few issues, including the front cover of Issue No. 13.

The ‘grey suits’ bit referred to the fact that the Beatles had adopted their black leather outfits in Hamburg and were the only Liverpool group to dress in that fashion. I assume that the Jim he refers to is Paul’s father Jim McCartney and it sounds as if Jim would have preferred his son to dress in a more conventional manner.

The Gestapo referred to are the Aliens Police in Hamburg, who caused George to return to Liverpool because there was a 10 o’ clock curfew for youngsters under the age of 18 in Hamburg and he was told he couldn’t join the others on stage after that time, no doubt reported by a frustrated Bruno Koschmider, furious at the rumour that they were going to take up a residency at the rival Top Ten Club.

It was a thrill for me, in 1997, to see that this piece I’d commissioned John to write for me had been given a new lease of life because it inspired Paul when he conceived his ‘Flaming Pie’ album.

As for the true origin of the name the Beatles: I was present in the Gambier Terrace flat when John and Stuart were discussing a name for the group. Since they’d junked the Quarry Men name, they’d tried a few unsatisfactory ones, such as Johnny & the Moondogs – and Casey Jones of Cass & the Cassanovas had even suggested Long John & the Silver Men!

It was Stuart Sutcliffe who proposed Beetles, his inspiration being Buddy Holly’s backing band, the Crickets. John later added the ‘a’, although they tried to use the name Silver Beats on one occasion, then the Silver Beetles, then the Silver Beatles, even the Beatals. It was in August 1960 that they finally decided on the Beatles – and it had nothing to do with the term Beat groups, because the term didn’t exist at the time and only came into being after Mersey Beat was established and we began to refer to the groups as Beat groups. There is also no truth in the rumour that it was inspired by a motorcycle gang in the 1954 film ‘The Wild One’ as this movie was banned in Britain for 14 years, until the late 1960s and the Beatles never saw it in those early days.

I was later to find that Buddy Holly had considered calling his group the Beetles prior to him naming them the Crickets!

Virginia’s Roundabout.

Virginia provided Mersey Beat’s gossip column and, obviously, it developed as we became increasingly involved in the local scene, visiting the clubs and artists seven nights a week.

It’s interesting at this stage that we thought there were more than three hundred groups in the city when the number was at least twice that amount. The Beatles had also told Virginia that a millionaire wanted them to play in Spanish clubs – but the details have been lost with the passage of time: who was the millionaire, what clubs were they, how much was the offer and why did they turn it down? It seems we’ll probably never know.

Another mention in the column was the Jim Gretty show at the Albany, Maghull. This was a three-hour variety show in aid of charity. Ken Dodd topped the bill and the Beatles also appeared.

Another act was the Country Music Group Hank Walters & the Dusty Road Ramblers. Hank recalled that John Lennon came up to him and said, ‘I don’t go much on your music, lad, but give us your hat.’ Walters told John that he didn’t think much of the Beatles’ music and they’d never get anywhere unless they got with it and played Country Music.

Ken Dodd also thought their music was terrible and made a complaint to the organizers. When Paul came into his dressing room and said they’d been told that if they gave him their card he might be able to get them some bookings, he threw the card away.

He was reminded of it years later when Paul McCartney mentioned that they’d worked with him before. ‘No, you’ve never worked with me, lad,’ Dodd told him. When Paul mentioned it had been at the Albany, Dodd said, ‘That noise wasn’t you was it?’ ‘Yeah, we were rubbish, weren’t we?’ ‘You certainly were,’ said Dodd, ‘I had you thrown off.’

Reminds me that when they appeared at the Pavilion as a skiffle group the Quarry Men, they were told to stop playing after 30 seconds!

Originally, I’d thought in terms of a ‘What’s On On Merseyside’ covering the vast range of music in the city. There were numerous jazz venues, country music clubs, folk clubs, clubs where poetry was read, and over 350 clubs linked with the Merseyside Clubs Association whose acts produced a mix of comedians, speciality acts and solo singers.

However, it soon became obvious that I was becoming more involved in the rock group scene and wanted to concentrate more on the hundreds of rock ‘n’ roll groups who existed and performed in cinemas, ice rinks, swimming baths, town halls, synagogues, church halls, ballrooms, cellar clubs and pubs.

This was a unique scene which was ultimately to affect popular music internationally via the Beatles and other groups in what came to be known as ‘The Mersey Sound’ or ‘The Liverpool Sound.’

Mersey Beat was initially a two-person effort, just Virginia and me, with outside contributions I commissioned from John Lennon and photographers Dick Matthews and Les Chadwick of the Peter Kaye Studio. Paul McCartney also sent me regular letters about their activities, which I also published.

This Is Mersey Beat.

Little did I realize, decades later, that when I was working, bleary–eyed, in a tiny little attic office at 2 o clock in the morning, a phrase I created for my newspaper would become part of the English language.

Time was approaching for the publication of the first issue and I still hadn’t thought up a suitable name for the paper. I rested back in the chair, trying to work out a title that would be appropriate for what I was going to publish. I closed my eyes and began to visualize. For one thing, I had to consider the area I would be covering. In my mind, I could see a map of the entire Merseyside conurbation – ‘over the water’ taking in Ellesmere Port, Chester, the Wirral, Birkenhead and New Brighton. On the Liverpool side of the river I would stretch right up to Southport, taking in Crosby and Formby and then surrounding Liverpool, I would also take in Runcorn, St Helens and Widnes.

Suddenly, into my visualization of the map came the image of a policeman. It clicked: a policeman’s beat! The entire Merseyside area would be MY beat and the name Mersey Beat popped into my head.

After several issues of Mersey Beat had been published, Cavern disc jockey Bob Wooler came into the office with Tony Crane and Billy Kinsley. He suggested that I give them permission to name their group after the newspaper. He said that the Melody Maker had a group named after it and it would be good publicity for me to have a group named after my paper. So, the Mersey Beats (later they truncated it to Merseybeats) were born. When Brian Epstein wanted to promote a series of concerts with several of his artists, he approached me for permission to call it ‘Mersey Beat Showcase,’ which I agreed to.

When John Schroeder asked me to record an introduction for a series of two albums he’d made with Liverpool groups, I wrote a brief piece and recorded it, ending it with the words “This then, is Mersey Beat” and gave John permission to call the albums ‘This Is Mersey Beat.’

However, the sound itself was never called Mersey Beat at the time. The media always referred to it as ‘The Mersey Sound’ or ‘The Liverpool Sound.’ For some reason, it was a after Mersey Beat had ceased publication that people began to refer to the sound as Mersey Beat – however, as it wasn’t called by that name when the scene was flourishing in Liverpool, it is an anachronism.

Written by: Bill Harry ©2019. All rights reserved.

No unauthorised copying or re-publishing of this material is allowed by law.

Please contact the writer for re-print permission.

(Contributor, McCartney Times)

There are no comments at the moment, do you want to add one?

Write a comment