What ‘Echo in the Canyon’ Misses About the Laurel Canyon Scene – Variety

Too much echo… not enough Canyon.

That’s at the core of the imbalances in the celebrated new rock doc “Echo in the Canyon”: It’s a movie with too much Beach Boys and Beatles — as strange as it seems to make a complaint of that — and not enough of the people who really lived in the Canyon. Too much time exploring the Hollywood recording studios, and not enough in the living rooms and backyards in those hills that gave life to the music.

And while this is at least in part a film about and spurred by the making of Jakob Dylan’s era-tribute duets album (coming in June and also titled “Echo in the Canyon”) and related 2015 L.A. concert, there’s too much 21st century and not enough 20th.

As most rock buffs know by now, the film, directed by long-time music manager and label executive Andrew Slater, tours the heady world of the Mamas and the Papas, the Byrds, Buffalo Springfield and others who created the folk-rock revolution of that time while forming a community shaped to the contours of the hills above Hollywood.

For many music insiders and fans who contributed to the very impressive opening weekend gross ($103,716 in just two theaters, touted as the second best per-screen average so far this year), a good deal of the chatter has been about not what’s in the movie, but what isn’t. Or more to the point, who isn’t — specifically Joni Mitchell, an artist as identified with the rich legacy of that landscape as anyone.

Others are defending the omission, if grudgingly, by noting that the movie limits itself to the time between 1964 (with the advent of the Byrds and the rise of folk-rock) through 1967 (when David Crosby was booted from the band and Neil Young left Buffalo Springfield, the other greatest band of that scene).

Both sides of that argument are partly right and partly wrong. Mitchell got there in late ’67, with Crosby producing her debut album at that time. But her impact didn’t come until later. Still, some mention of the next era, growing from this scene’s ashes and revolving around visionary singer-songwriters rather than bands, would have been very helpful.

Arguably more troubling is there being no presence at all of the Doors, nor of Love, two bands crucial to that community. And there’s virtually no look at the larger context of the times’ cultural turmoil with the civil rights and anti-war movements and the Aquarian hunger for belonging and hope — and the new vistas of artistic expression that sprung from it all.

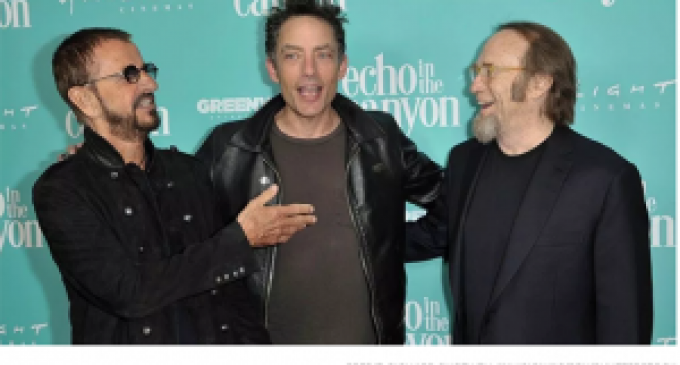

As for what is in the film, there is much to love, not least the music at its core and insights and anecdotes from those in, around and closely following in the footsteps of that scene: Stephen Stills, Michelle Philips, Roger McGuinn, David Crosby and Graham Nash among those in the first group, Brian Wilson, Eric Clapton and Ringo Starr in the second, and Tom Petty and Jackson Browne leading the latter. The assertions made that the canyon was to its time and milieu equal to fin-de-siècle Vienna, Paris’ Movable Feast or even Hollywood’s Golden Era are at once grandiose and a bit myopic, of course, but that’s largely forgivable.

The non-musical highlights by and large are the vivid tales of that life. Stills lights up the screen talking about neighbor Frank Zappa standing in the street between their houses and reciting the lyrics to his song “Who Are the Brain Police?,” and sheepishly admitting that he fled out the back one time when the cops came to his house while Eric Clapton, Neil Young and others were visiting. McGuinn shared some great glimpses into the genesis of L.A. folk-rock. Crosby brought his unsparing perspective to it all — not least in admitting that he wasn’t kicked out of the Byrds because of musical differences, but because he was a jerk. And Graham Nash often seems on the verge of tears as he recounts those times with unbridled affection for the place that took him in and opened up new worlds.

But what was being in that world really like — the energy of the spontaneous get-togethers and drop-ins at neighbors houses in which songs were created and shared, the chance encounters at the Country Store or other places that led to collaborations, the romances and breakups that inspired many songs, the drugs that enlivened and destroyed the creative environment? Certainly there are plenty of non-musicians who were there who could have shared their memories to fill out the artists’ pictures. (There are several books and movies that paint that picture thoroughly, including Michael Walker’s 2007 book “Laurel Canyon: The Inside Story of Rock-and-Roll’s Legendary Neighborhood,” Harvey Kubernik’s 2009 tome “Canyon of Dreams” and portions of Barney Hoskyns’ 1996 “Waiting for the Sun: A Rock & Roll History of Los Angeles.”)

Instead. there are staged coffee-table chats with Dylan, Regina Spektor, Beck and Cat Power, all whom were part of the 2015 film and/or recording projects, all artists of great merit with legitimate claims on influence from the ‘60s Laurel Canyon world. But their contributions to the discussion are notable for their near-complete lack of meaningful insights, sans anything on how it all impacted them — no fond memories of hearing these songs for the first time, or of playing them when they were starting out, or looks at how they influenced their own writing. And, again, there was so much about the Beach Boys and Beatles, particularly how they influenced each other — fascinating, but not exactly revelatory, and only tangential to the real topic at hand.

As for young Dylan, his quiet reserve as well as his personal/professional legacy seem to open up trust in those he interviewed. But it also means he’s not exactly a dynamic presence and we never get a sense of passionate curiosity, though his reverence is clear. As well, he gives no real sense of how this music impacted him and his own art, as if maybe he was reluctant to tie his lineage to his interest in the topic. There is, though, one cagey bit in which Crosby talks about the Byrds doing “Mr. Tambourine Man” and says that Dylan showed up, to which the younger Dylan deadpans that Crosby needs to be more specific.

On the whole, it seems as if Slater and Dylan were not sure what they wanted the movie to be. If it was about the making of the album and/or concert, then structure it that way, with those ventures inspiring the exploration of the culture and personalities behind the songs. If it was, indeed, about life in the Canyon being comparable to that in Gertrude Stein’s Paris, then a stronger, deeper case needed to be made.

And then there were clips from the 1969 movie “Model Shop” by French filmmaker Jacques Demy set around Laurel Canyon and featuring an appearance and soundtrack music from the band Spirit (another noteworthy band not mentioned in “Echo.” Why were we seeing this? What were we supposed to learn from it? What was that movie even about? None of that was discussed at all and those bits just took time that could have been used for deeper digs.

But, of course, there are the songs! Treasures all, especially in their original forms. Curiously, one that resonated after seeing the movie was the Byrds’ “Goin’ Back,” written by Gerry Goffin and Carole King just after King moved to the Canyon. The song supplanted Crosby’s menage-a-trois ode “Triad” on the 1968 “The Notorious Byrds Brothers” album, ramping up tensions that resulted in him being fired from the band in late 1967. The song’s nostalgia for a time gone — an era passed into the haze — is a perfect epitaph for these echoes.

Source: What ‘Echo in the Canyon’ Misses About the Laurel Canyon Scene – Variety

There are no comments at the moment, do you want to add one?

Write a comment