Astrid Kirchherr: a stylish outsider who saw beauty in the Beatles | Art and design | The Guardian

As the various obituaries that marked her passing testify, Astrid Kirchherr’s fate was to be forever associated with the Beatles, a group she met almost by accident and whose image she remade so audaciously.

It was Kirchherr’s boyfriend, Klaus Voormann, who insisted that she and their friend, Jürgen Vollmer, came with him to the spectacularly seedy Kaiserkeller in Hamburg’s red-light district on an October evening in 1960. The previous night Voormann, a jazz fan who had never attended a rock’n’roll gig before, had been mesmerised by the Beatles’ raw on-stage energy as they performed to a motley crew of drunks, sailors and prostitutes. Kirchherr, though, immediately saw something else in them. “I was amazed at how beautiful they looked,” she said, later. “It was a photographer’s dream, my dream.”

Kirchherr had just completed a photography course at the College of Design and Fashion in Hamburg, where her tutor had been Reinhart Wolf, who would later become an acclaimed photographer of architectural facades. On graduating, she worked as his assistant for a further three years, but her abiding interest was the architecture of the human face.

As a photographer, Kirchherr was a quietly confident woman in a predominantly male world. A modernist at heart, she shot her subjects in stark monochrome, insisting that serious photography was essentially a black and white medium. “She always worked with a tripod,” Voormann recalled years later, “and always positioned the people, giving them directions.”

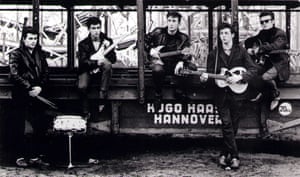

That meticulous approach is evident in her famous early portrait of the Beatles in an empty, neglected Hamburg funfair, which was made just days after she first met them. The Beatles were living a hand-to-mouth life at the time, playing several sets a night, drinking hard and sharing dingy rooms in an unsavoury neighbourhood. She thought the “slight grubbiness” of the location suited the way they looked. She was correct.

Lined up against a dilapidated fairground structure, they look like a bunch of street toughs with guitars. Their studied insouciance is undercut by their stern gazes, which are directed at the camera or off into the distance. On that early shoot, working without an assistant, she instructed them how to look and where to look, despite having only a rudimentary grasp of English. She later said, “I took their heads in my hands and arranged them as I wanted them.”

In her early photographs of the group, it is Stuart Sutcliffe, who looks the coolest and the most mysterious, his black clothes, upright quiff and shades a timeless style that echoes through punk, post-punk and beyond. (Lennon instinctively understood his friend’s star quality, insisting in the face of the other’s complaints that he remain in the group despite his rudimentary musical skills: “It doesn’t matter, he looks good.”)

Lennon dubbed Kirchherr and her friends “the exies” – scouse shorthand for existentialists – and may have initially been slightly threatened by their studied cool, sophistication and style. Sutcliffe had no such reservations, connecting with the young Germans immediately and referring to them as “real bohemians”.

It was with Sutcliffe, the artiest Beatle, that Kirchherr connected most deeply: the two soon became lovers and moved into a loft space in her mother’s house. She undoubtedly shifted his perspective away from pop music and back to art. To Lennon’s consternation, he soon left the group to concentrate on his first love, painting. Before that, though, he was her template for all that followed in terms of the Beatles change of style. She moulded him to a degree in her own image: the bobbed hair, the more tailored leather jackets, the black polo necks. It was a radical shift away from the influence of recent pop past – 1950s rock’n’roll – to the modernist present: French New Wave cinema, art school bohemianism, a hint of androgyny.

Sutcliffe was the first Beatle to change his hairstyle having seen and been impressed by Voormann’s longer tresses, which had been sculpted by Kirchherr to help conceal his prominent ears. Harrison soon followed suit. Intriguingly, Lennon and McCartney were the most reluctant to give up their quiffs. On a visit to Paris, they were finally convinced by Vollmer, who was then working as an assistant to the American photographer, William Klein – which gives us some idea of the circles these young German bohos were moving in.

In applying her bobbed-hairstyle, borrowed from Juliette Gréco, to the working class lads from Liverpool, Kirchherr feminised them in a way, softening their street-tough image. It was a bold move that announced the impending pop future, the group’s longer hair later becoming an obsession to the mainstream media, who christened them, not altogether flatteringly “the Mop-tops.”

Much deeper cultural shifts were under way, though, and the Beatles came to represent a wave of meritocratic creativity in music, art, film and photography that, for a brief moment, made the mid-60s seem genuinely utopian. As pop historian Jon Savage has noted, the Beatles, in their irreverent attitude and modernist style almost as much as their early music, signalled “the end of the Victorian age” in Britain. Ironically, it was a young German woman with an emphatically European aesthetic who shaped their image.

Kirchherr’s relationship with Sutcliffe was intense and short-lived. Soon after they began living together, he began attending art school in Hamburg and painted with a renewed energy despite being dogged by debilitating headaches. It is hard now to grasp how tumultuous his sudden death, aged 21, was for her at a time that promised so much.

Lennon, too, was devastated at the loss of his close friend. When he and Harrison visited the loft studio, he asked Kirchherr to photograph him standing in the same spot that Sutcliffe had stood in for a previous portrait by her. There is a palpable sadness that emanates from her image of a shell-shocked Lennon standing in the ghostly half-light, but she much preferred another portrait she made in the same session. In it, John is sitting in a chair and George is standing behind him, his hand resting on his friend’s shoulder. “Every time I see that photo, I see the immense sadness in John’s face and the strength in George,” she later said.

As time has gone by, it is other less well-known portraits by Kirchherr that seem more striking, including an almost deadpan self-portrait, in which she stares straight ahead, holding the camera’s shutter release, beneath thin branches that hang down from somewhere above her head. Writer and art critic Michael Bracewell has pointed out that her androgynous look and cerebral approach harked back to “the young German modernists of 1929”, while a later snapshot of her then husband, Gibson Kemp, at the Star Club in Hamburg, could be mistaken for “a photograph of Nico and Sterling Morrison” hanging out at Andy Warhol’s Factory.

In many ways, the young Kirchherr was an outlier, a stylish bohemian who understood the ways in which art could impact on popular culture, and vice versa. In a dingy, disreputable Hamburg bar, amid the noise and the squalor, she detected something beautiful. She was in the right place at exactly the right time. And so, more to the point, were they.

- This article was amended on 19 May 2020 to correct the names of Juliette Gréco and Gibson Kemp.

Source: Astrid Kirchherr: a stylish outsider who saw beauty in the Beatles | Art and design | The Guardian

There are no comments at the moment, do you want to add one?

Write a comment