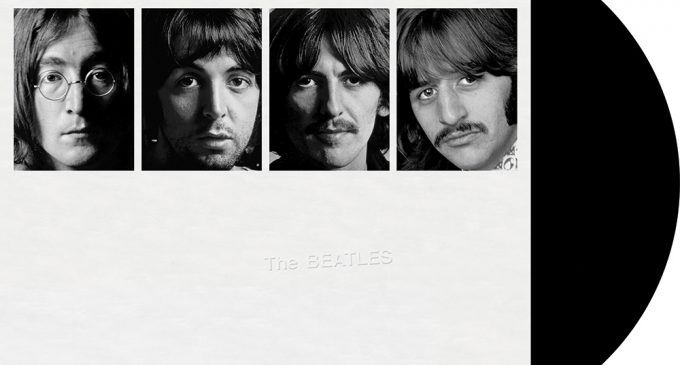

The Beatles’ struggle to finish “The White Album”: How bad did it get? | Salon.com

Excerpted from “Sound Pictures: The Life of Beatles Producer George Martin (The Later Years: 1966-2016)” by Kenneth Womack; Chicago Review Press, September 4, 2018 As the summer of 1968 wore on, George Martin and the bandmates logged increasingly long hours in the studio. Paul McCartney had debuted a new, playful composition called “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da.” Of all the songs that they would attempt that summer, “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” revealed the inherent limitations of the group’s painstaking rehearsal and recording practices. Over the ensuing days, the new song would be the subject of successive remakes as McCartney and the other Beatles made marginal strides toward capturing his vision for the song. By July 5, Paul attempted a reggae version of the song, with George hastily recruiting a trio of saxophonists and a bongo player for the session. Seemingly mad for effect, Paul asked for a piccolo superimposition later that same evening, only to wipe it from the mix shortly thereafter. Before the session was out, the Beatle had replaced the woodwind instrument with a guitar overdub. But to producer Chris Thomas’s mind, the guitar superimposition made little sense, as “Paul was deliberately overloading the sound through the desk so that it sounded like a bass.”By the following Monday, McCartney arrived in Studio 2 ready to remake “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” once again. In short order, the work of Martin’s session men was scrapped in favor of a new basic track featuring McCartney’s fuzz bass, Ringo Starr’s drums, George Harrison’s acoustic guitar, and John Lennon’s piano. By this point, the morale among Martin’s production team—not to mention his own—was decidedly low. As Richard Lush later recalled, “They spent so much time doing each song that I can remember sitting in the control room before a session dying to hear them start a new one. They must have done ‘Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da’ five nights running and it’s not exactly the most melodic piece of music. They’d do it one night and you’d think, ‘That’s it.’ But then they’d come in the next day and do it again in a different key or with a different feel. Poor Ringo would be playing from about three in the afternoon until one in the morning, with few breaks in between, and then have to do it all over again the next night.” Before the Monday night session mercifully concluded, McCartney had revised his vision for “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” yet again—this time, opting for a Latin American feel in place of the track’s earlier reggae sound. Amazingly, the next evening the song finally began to come together, with the bandmates enjoying a convivial session, complete with pervasive laughter and inside jokes. With “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” holding steady for a change, George and the Beatles turned back to “Revolution 1”—only John had something else in mind for his composition. Since early June, he had maintained that “Revolution 1” should be the band’s next single. But Harrison and McCartney, in particular, vetoed the idea. “They said it wasn’t good enough,” Lennon later recalled. To his mind, they “were resentful and said it wasn’t fast enough.” And Martin, perhaps inadvisably, had taken Harrison and McCartney’s side in the ongoing squabble. As engineer Geoff Emerick later recalled, “In the early days, George Martin had picked the songs that would comprise the A-side and B-side of a Beatles single. But by this point in their career, it would be the group’s decision; George might offer some input or suggestions, but it was their final call.” John’s solution to the dilemma was obvious to his way of thinking—call their bluff, speed up the song, and release it as the next Beatles single posthaste. With the Maoist revolution in full flower and the Vietnam conflict raging overseas, Lennon felt that the Beatles were duty bound to join the political fray, to take advantage of their bully pulpit and comment on the international malaise.During a July 9 session, Lennon led the other Beatles on a new recording of “Revolution 1,” with the faster, hard-rocking version to be titled simply “Revolution.” Lyrically, the compositions were almost identical but for a single word. As John later recalled, “There were two versions of that song, but the underground left only picked up on the one [the faster version] that said, ‘count me out.’ The original version, which ends up on the LP, said, ‘count me in,’ too; I put in both because I wasn’t sure.” After rehearsing a basic track featuring Harrison and Lennon’s electric guitars, McCartney’s bass, and Starr’s drums, they remade the song on July 10. That evening, Martin produced a searing version of “Revolution” for the ages. As the producer later remembered, “We got into distortion on that, which we had a lot of complaints from the technical people about. But that was the idea: it was John’s song and the idea was to push it right to the limit. Well, we went to the limit and beyond.” As Phil McDonald later noted, George captured the blistering sound by feeding the guitar signals through the recording console. “It completely overloaded the channel and produced the fuzz sound,” McDonald reported. “Fortunately the technical people didn’t find out. They didn’t approve of ‘abuse of equipment.’” After capturing “Revolution” in ten takes, the bandmates applied overdubs to the recording, including a series of handclaps and a sizzling, double-tracked lead vocal from John. The next evening, Thursday, July 11, witnessed an additional overdub courtesy of keyboard session man Nicky Hopkins, who superimposed a magnificent electric piano solo onto the track. And with that, Lennon’s “Revolution” was complete.

He had met, if not exceeded, his self-imposed burden of imagining a faster version of the song, and in so doing he had duly presented “Revolution” as the lead contender for the next Beatles single.

In many ways, the ball was now in Martin’s court. While the Beatles had clearly taken ownership of their artistic direction, even assuming a greater role in the production of their music from ideation through remixing, the band’s producer was often forced to weigh in with his own perspective in order to settle their differences of opinion. And “Revolution”—a song to which George himself was clearly partial—was setting up the Beatles and their inner circle for a showdown. As mid-July came and went, George and the bandmates completed several more tracks, including Ringo’s “Don’t Pass Me By,” which had been waiting in the wings.

During the week of July 15, the tensions that had been brewing among the bandmates and their production team finally came to a head. The Monday night session in Studio 2 began, ominously enough, with McCartney returning yet again to “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,” for which he recorded a new lead vocal, eating up considerable studio time in the process. Working until three o’clock in the morning, the Beatles then devoted more than two hours to rehearsing a new Lennon composition titled “Cry Baby Cry,” with its nursery-rhyme lyrics and somber tones. But earlier that same evening, all hell had broken loose during McCartney’s efforts to perfect his vocal. Only this time, the fireworks weren’t emanating from among the Beatles, with Yoko in tow, as always, down in the studio. Strangely, the blowup occurred upstairs in the control booth, and the central player was Geoff, the timid and unfailingly respectful sound engineer for the Beatles’ most innovative recordings. And perhaps more importantly, he was Martin’s right-hand man throughout the ups and downs along his journey with the group.

It all started, innocently enough, as Emerick and Lush engineered McCartney’s latest stab at singing “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da.” As Geoff later recalled, “Richard and I began the long, tedious process of rolling and rerolling the tape as he [Paul] experimented endlessly, making minute changes to the lead vocal, in search of some kind of elusive perfection that only he could hear in his head.” And that’s when George chimed in, offering advice to the Beatle about rephrasing his vocals. “Paul, can you try rephrasing the last line of each verse?” George asked. To Geoff’s ears, the Beatles’ producer was adopting the same “gentle, slightly aristocratic voice” that he had always deployed in his dealings with the Beatles. Geoff couldn’t help admiring the older man, later lauding him for “still trying to do his job, still trying to steer his charges toward increased musical sophistication and help push them to their best performances.” But Emerick wasn’t prepared for McCartney’s curt response: “If you think you can do it better, why don’t you fucking come down here and sing it yourself?” The engineer sat there in the booth, dumbstruck by Paul’s tone. “What happened next shocked me to the core,” Emerick later wrote. “In sheer frustration, quiet, low-key George Martin actually began shouting back at Paul. ‘Then bloody sing it again!’ he yelled over the talkback, causing me to wince. ‘I give up. I just don’t know any better how to help you.’ It was the first time I had ever heard George Martin raise his voice in a session. The silence following the outburst was equally deafening.”

For Geoff, George had suddenly crossed a line. While his colleagues at Abbey Road often referred to him affectionately as “Golden Ears” or “Ernie,” others called him “Emeroids” in a crude reference to his tendency, during extreme occasions, to be overwhelmed by his anxiety. And in this moment, after witnessing George going toe-to-toe with his clients, the engineer’s disquiet had reached a fever pitch. Emerick knew, in his heart, “that was it for me. I sat at the mixing console and continued to man the controls, even though every fiber in my body was screaming, ‘Get out! Now!’”

The next afternoon, as George was making preparations for the upcoming session, the engineer made his intentions known. After having tossed and turned the night before, a sleepless and dejected Emerick walked into the control room. “I took a deep breath,” Geoff later wrote, “and at last the words came out. ‘That’s it, George,’ I announced. ‘I’ve decided I can’t take it anymore. I’m leaving.’” For his part, Martin was thunderstruck. “You can’t leave in the middle of an album,” he told the engineer, who replied, “I can, George, and I am.” With Martin hot on his heels, Emerick made his way to Alan Stagge’s office to announce his decision to quit working Beatles sessions. With George openly sympathizing with Geoff’s frustrations, the studio head asked Geoff to finish out the week before rotating to another artist. But Geoff wouldn’t hear of it. With no other choice, Stagge gave him the rest of the week off and pressed Ken Scott into service as his replacement. For Geoff, the mere notion that he had been liberated from the toxic atmosphere with the Beatles was sweet relief. But for George, as he made his way back to Studio 2, the situation had suddenly been rendered even bleaker than it had been before Geoff’s desertion. Until that point, Martin had been able to hide behind his newspapers and allow the moveable feast of the Beatles’ discontent to roll on without him. But now, with Emerick gone, he was suddenly very much alone up in the booth. When he made his way down into the studio after Emerick had bade farewell to the band, Martin supervised ten takes of “Cry Baby Cry” and even pitched in with a nifty harmonium part.

If George felt a sense of hollowness in the wake of Geoff’s sudden absence in his life with the Beatles, it may have been—in retrospect—decidedly short lived. For his part, Scott acted as a kind of emollient for the tension that had overwhelmed the bandmates’ atmosphere. Easygoing and unflappable in contrast with the bashful, high-strung Emerick, Scott may have been just what Martin and the Beatles needed to finish off their new long-player. “I was much more of a basic rock and roll type engineer than Geoff was,” Ken later recalled. To his mind, it was clear that “they wanted more of a rock and roll album. With me coming in at that point, it worked out perfectly.” There were still “moments of tension” with Scott in the engineer’s chair, to be certain, “but the majority of the time we had a blast. It was such good fun!” Scott added, suggesting that his participation “gave them what they were looking for at that point, so they could relax and have more fun.” George certainly wasn’t averse to having more fun with the Beatles in the studio. But by this point, the heady days of making Sgt. Pepper seemed like a distant memory.

Source: The Beatles’ struggle to finish “The White Album”: How bad did it get? | Salon.com

There are no comments at the moment, do you want to add one?

Write a comment