Making Mull Of Kintyre: Paul McCartney takes us to High Park Farm 40 years on

The long and winding road that leads to Paul McCartney’s High Park Farm on Kintyre runs down the western spine of the peninsula past crashing Atlantic waves before climbing through forests and fields into the hills above Campbeltown.

It was there in 1968, inspired by the drive to his Scottish rural bolthole, that the world’s most famous and successful pop star wrote The Beatles song of the same name which would become their ill-starred final single in May 1970.

By then, the greatest band that ever was had already broken up, and McCartney had retreated into seclusion and sunk into a depression. Little could he have realised that, on the same patch of land, the seeds of his enormously happy and successful post-Beatles reinvention would be sowed and reaped.

Hidden from screaming fans and the prying media, the privacy and relative anonymity of High Park Farm and Kintyre gave McCartney his life back in many ways. Especially once his first wife Linda Eastman – a respected New York rock photographer, musician, pioneering vegetarian and animal rights activist and horse-loving country girl at heart – fell in love with the place and encouraged McCartney to make it their back-to-basics place of respite from the world. It would remain so until Linda’s death from breast cancer in 1998.

There, Paul and Linda led the good life and dreamed it all up again, replenishing themselves with long summers messing about in wellies, raising their four kids and some seriously lucky livestock (no danger of the slaughterhouse at the McCartney farm).

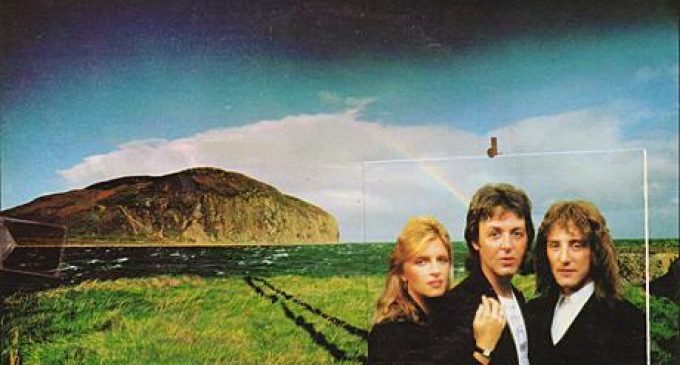

In 1971 they formed Wings with ex-Moody Blues guitarist Denny Laine – who would bed down in an old cottage nearby whenever he visited – and they would write, rehearse and record together in a converted barn studio dubbed Spirit of Ranachan. In return for what Kintyre gave him, McCartney – with a little help from his friends – gave Kintyre one of the most unabashedly romantic, not to mention vastly successful songs in the history of music.

“Mull of Kintyre, the whole area of Kintyre and Argyllshire, is very special because of the memories it holds for me and the family,” says McCartney, speaking to The Big Issue four decades on. “It’s really nice to think that the love we have for the area was captured in a song and brought to the attention of many people around the world.”

A cosy-jumper acoustic ode to the mist rolling in from the sea and his desire always to be by his chosen corner of Scotland’s weather-beaten west coast, 40 years ago Paul McCartney and his band Wings’ Mull Of Kintyre became the biggest and – arguably – best Christmas No 1 of all time. It’s shortbread tin tartan cheesy, sure, and no doubt scornfully remembered by children of glam rock and punk. But leave your cynicism at the gate, and when it crests with a vaulting key change as the stirring drones and military drums of the Campbeltown Pipe Band enter, it’s enough to give tingles to your tingles’ tingles.

Mull Of Kintyre is among the 50 biggest-selling singles of all time worldwide

At an estimated nine million copies sold worldwide – despite having never being released as a single in America – Mull Of Kintyre is among the 50 biggest-selling singles of all time worldwide, and a bigger-selling single than any other that McCartney has ever penned, the entire Beatles catalogue included save for I Want To Hold Your Hand. It spent nine weeks atop the chart, becoming the first UK single to sell over two million copies. It remained the biggest-selling British single of all time until usurped by Band Aid’s Do They Know It’s Christmas? in 1984, on whose B-side McCartney featured, funnily enough. It’s still comfortably the biggest-selling non-charity Christmas No 1 of all time.

Mull Of Kintyre was a hit so geologically massive it practically put Kintyre – an obscure part of Scotland hitherto best known for Second World War and Cold War military installations and its dwindling whisky and fishing industries – on the map. And yet, homegrown right there in situ on the farm – some of it even recorded in the open air – the song’s creation was humble and heartwarming.

“I’ll give you a wee bit of banter,” shares John Brown, as we trudge through the shingle on Saddell Bay beach, as his spaniel scurries around our heels. “We knocked Abba off of No 1,” he grins. “That’s my claim to fame.” So far as brags go for a then 16-year-old shipyard boy and junior member of the Campbeltown Pipe Band, that can have been no average way to impress the girls.

“I remember as if it were yesterday, McCartney coming through the door with his cowboy boots on,” Brown reflects of his first encounter with the actual living, breathing Beatle from up the road. “And then we got stuck into the recording. It never took long neither.” Further along the beach we meet up with two of Brown’s fellow once-junior members of the Campbeltown Pipe Band, piper Ian McKerral and drummer Tommy Blue. All three of them are now in their late 50s, and blessed with significantly less of the hair that they each wore long as teenagers in the late Seventies.

At the time we didnae really realise how big it was gonnae be,” remembers McKerral, “I don’t think anybody did

McKerral describes the day in July 1977 when their Pipe Major, the late Tony Wilson (who died in 1994), walked into practice and made an unforgettable announcement. “I remember Tony coming into the hall,” he recounts, “and saying ‘I’ve been up at McCartney’s, he’s wanting us to come and record this single’. We all burst out laughing, ’cause we thought it was a wind-up. But it was true enough. So we learned the piece and up we went and recorded it, and the rest is history.”

Well drilled, the band nailed it in one take, which, cleverly, was recorded outside for added natural echo from the surrounding landscape. “At the time we didnae really realise how big it was gonnae be,” remembers McKerral, “I don’t think anybody did.”

“We all got demos sent to the houses after we made the record,” says Brown, “and that was the first time we heard everything together. The guitar and the vocals and him wi’ his bass guitar and everything. Straight away when you heard it, right enough, you thought ‘oh hold on, this is something else, this is clever’.”

All involved would be reunited a couple of months later to make the iconic Mull Of Kintyre video at Saddell Bay. Almost exactly 40 years to the day after the shoot occurred, Brown and McKerral take out their pipes and start playing, and once again Mull Of Kintyre’s charmed melody drifts over the same sands where the pipe band had trudged up and down in formation in full Highland regalia for multiple takes, as an autumn chill nipped at their bare knees. Busloads of extras would later arrive from Campbeltown for the final campfire singalong scenes, and a party atmosphere prevailed. Whisky flowed and barbecued food was served. Nobody can exactly remember whether the sausages were veggie.

Ignoring the small technicality of not being filmed at the actual Mull of Kintyre – the peninsula’s steep and panoramic headland being in fact several miles round the coast, which understandably often confuses tourists – the Mull Of Kintyre video is sweet in its simplicity and innocence, and, as I come to realise, stories the making of the song. McCartney perches on a gate before a white cottage, strumming and singing the opening chorus while gazing wistfully seawards, before hopping down and strolling over to Laine, who hovers just out of shot with his guitar.

Linda later wanders in from the background to add her harmonies, and the whole party moves out on to the beach to face the pipe band coming into frame as the camera swings around, the baton-twirling pipe major at their front and Saddell Castle off in the distance to the rear. It’s a literal representation of a musical coming-together which Mull Of Kintyre’s co-writer Laine remembers as being precisely when “magic” happened.

Mull Of Kintyre had begun life over breakfast on a summer’s morning in 1977, recalls Laine, who chats to me by phone from his home in New York. After his usual 10-minute drive up the track from his cottage to McCartney’s house that morning, Laine had found Paul toying with the opening bars of a promising new composition. “I heard the chorus and went ‘that’s a great song man’,” he remembers, his broad Brummie twang still well intact despite years of living in the US, where he continues to regularly tour and release music.

“He said ‘well I’ve only got this bit’,” Laine goes on. “So the next day we got a bottle of Famous Grouse whisky at some pub, and we went over to the cottage I was staying at and we wrote the rest. We sat out on the steps just looking at the mountains and all of the countryside around us, and wrote the song about that.”

I’m not sure about writing a Scottish song – how it would go down with Scots?

Laine was certain they had a potential hit on their hands, but McCartney seemed hesitant. “He said: ‘I’m not sure about writing a Scottish song – how it would go down with Scots?’,” Laine remembers. So they sought to add some extra authenticity by ringing up the local pipe band in Campbeltown. Pipe Major Wilson travelled up to the farm and helped them work out the score, which necessitated a fateful spot of compositional ingenuity. Mull Of Kintyre had been written and recorded in the key of A, but bagpipes can only play in B flat or E flat – meaning a bold switch of key was needed midway through.

“That was like an act of nature and magic that that happened, really,” enthuses Laine. “That was not something we could have worked out – they kind of brought that to us. And that’s what gave the song a boost. The hairs on the back of the neck…as soon as the pipes came in, away they went. When the pipes went on to the recording, I just thought, ‘that’s it, this is going to be huge’.”

It would go on to become huger than anyone could have predicted. “It felt as if the whole town was at No 1,” recalls piper Brown, of those nine weeks that Mull Of Kintyre made the Campbeltown Pipe Band the most famous pipe band in the world. “It was amazing,” drummer Blue agrees. “I remember the record shops with the queues,” adds McKerral.

To this day Mull Of Kintyre and the legacy of the McCartneys continue to bring in tourists and benefit the area in ways large and small. The annual Mull of Kintyre Music Festival owes its name to the song. The newly refurbished and reopened historic Campbeltown Picture House was saved many years back thanks in part to money donated by the McCartneys. Near the cinema lies the Linda McCartney Memorial Garden, established by a charitable trust formed in Linda’s name after her death and featuring a brass statue donated by Paul of his late wife holding a lamb. Humble, approachable and genuinely fond of Kintyre by all accounts, she’s well remembered around the town.

The only slight twinge of regret the pipers will admit to, as tends to be the way with huge hit songs, comes down to money. Given the choice of a lump sum or a percentage of the royalties, the pipe band committee opted for the upfront payout, having failed to foresee what a smash Mull Of Kintyre would become. Were royalties from the single still rolling into the Campbeltown pipers’ bank accounts today, I might have found them on a beach much more tropical than chilly Saddell Bay 40 years on. But they seem philosophical about it.

“We’d have done it for nothing to be honest with you,” states Brown proudly. “We got nae regrets,” says McKerral. “After all,” he adds, with a rueful smile and glint in his eye, “it’s only money.”

As for McCartney’s reflections on Mull Of Kintyre at 40? “I wrote the song when I realised there were no new Scottish songs being written,” he recalls. “It was a great experience recording it with the local pipe band and really exciting to see the amazing success it had in the charts at the time, so those memories mean I still love it and it’s a very special song for me.

“It had been great recording it with the pipe band and so to come together again for the video was so much fun for me and Linda. It gave us the chance to reminisce about the recording session and have a laugh.”

Following Linda’s death, McCartney – twice since remarried – has been seen on the farm less and less. Does it still hold a special place in his heart and will he and his family ever return? “We had such great times there,” McCartney recalls, “and I like to think from time to time that we’ll be able to get back.”

He will, I’m certain, always be welcome home to Kintyre.

Main image: Louise Haywood-Schiefer

Source: Making Mull Of Kintyre: Paul McCartney takes us to High Park Farm 40 years on

There are no comments at the moment, do you want to add one?

Write a comment